Wick-Rites I

Lillian Patch - 𝌜𝌷

“‘I have seen, and, look, a lampstand all of gold and a bowl on its top, and its lamps were on it, seven pipes for the lamps on its top. And there were two olive trees by it, one to the right of the bowl and one to its left. [...] These seven are the eyes of the Lord that roam through all the earth.’” (Zechariah 4:2–3, 11).

It is the enduring practice of the Akkoaic Temple to finish their weeks out of time.

The Temple has long been the odd one out among Neo-Lemurian entities in making use of a system of dates not based on the zygotriadic calendar. At the time of its foundation and in its early years, the Temple had no access to Muvian time-keeping systems, which had not yet come into North American public discourse. In fact, the Temple had little interest in “keeping time,” so to speak, at all, calendrics being understood as a psychiatric, political operation. Yet the Temple has long organized itself along a system of “weeks.” Why?

A Temple week, to the chagrin of historians of the Temple, is not a heptad of planetary rotations on its axis. In Akkoaic eyes, there were decades before their foundation in which not one week ever passed, and single terrestrial weeks in which decades of Temple weeks elapsed. To the Akkoa, a week is nothing but a ritualization of a “long path” of the lemurs—one of the paths of the numogram consisting of seven tests. When any of these five paths, the longest the numogram has to offer, elapses through a sevenfold ritual instantiation, a week is said to have passed; and with the completion of the section of each test, a day comes and goes.

An enormous amount of ink has been spilled on the five forms of the week, much of which is close to incomprehensible without prior knowledge. What there is, at least, a basic consensus on is their English names. Of the five paths, two are known as the long paths to love and two as the long paths to the temple. The former are known by their terminal test of 90, with “love” derived from its AQ of 90, while the latter end in the test 36, with “temple” abbreviating “temple of Lemuria” with an AQ of 306. Of each of these two, one path is deemed “anointed” and the other is deemed “submerged,” the latter beginning with 45 or 27—tests which no path arrives at if it does not begin there—and the former beginning with 54 and 72—which can be reached from another syzygy. The final path is the long path to the law—“law,” AQ 63, denotes its end in 63—which is numerically halfway between “anointed” and “submerged,” its initial 41 being possible to arrive at from elsewhere but not in its unambiguous form as a beginning. This path is often seen as specially exalted above all others.

While the Temple remained in large part confined by psychiatric institutionalization, resources were highly limited and led to the proliferation of many ad hoc ritual methods, now largely forgotten, for iterating the tests. However, after some of its members were able to go free, it became possible to more greatly standardize ritual practice. In this stage of development, the seven-armed candelabrum became the most prominent representation of the long paths. How exactly this came about is not exactly known, although it has been told in folklore many different ways and fabled about in stories of Edna’s Candlestick. What is known is that in this period a numogrammatic mapping onto a seven-armed candelabrum was widely disseminated and regularly used to invoke the long paths, and that this system is still in use today.

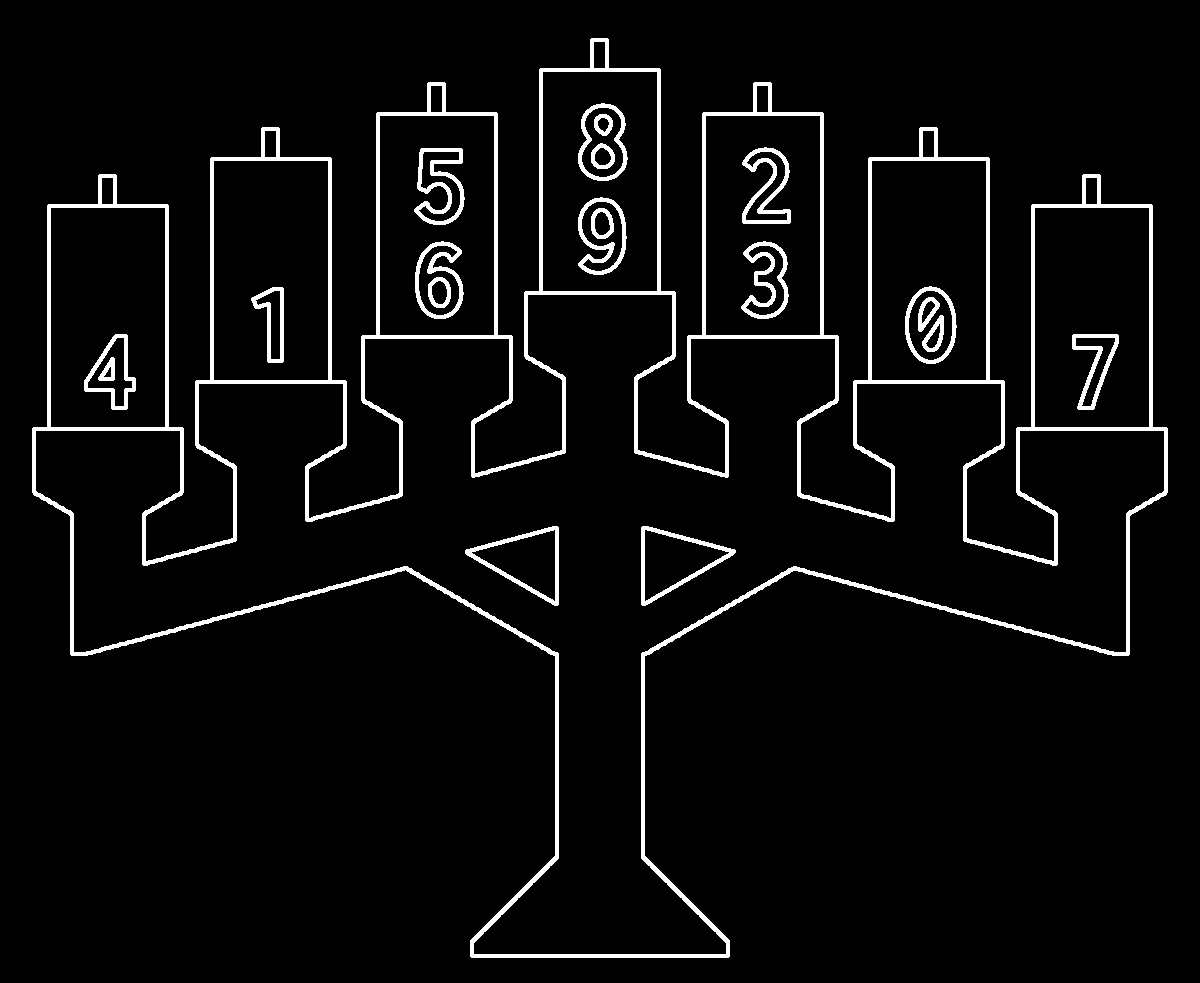

The Akkoaic mapping works as follows. Each syzygy is poised on two candles, one candle to each zone. 5::4 is stretched out on the left, between 4 on the leftmost candle and 5 on the left candle closest to the centre. 7::2, likewise, runs along the right, with 7 as the rightmost candle and 2 on the right candle closest to the centre. 6::3 is balanced in the middle, with 6 sharing a candle with 5 on the left and 3 sharing with 2 on the right. Zones 8 and 9 share the central candle, with zone 1 taking up the centre-left and zone 0 taking up the centre-right.

When lit, however, the candles do not represent zones but, rather, tests. A path begins by placing a mark of some sort on the candle of a zone—Edna Veil is said to have placed a ring on the drip edge of the candlestick holder. For the syzygetic paths of twinned tests, the relevant candle is that which lies between the two zones of the syzygy; after having been marked, it is immediately lit and the rite is complete. For all other paths, however, it is not the marked candle but its left or right neighbour which is to be lit first. For the candle on the extreme left or right, the other extreme is its other neighbour. If the candle which is closer to the mark’s syzygetic pair is lit, the initial test passes from the marked zone to its twin; otherwise, the first test passes from the marked zone to the terminus of its gate. By this process, the first test is initiated.

The first test being complete, there are in all cases at most two possibilities to succeed it; when this is the case, one test is of activity or patience (passing through a syzygy or its current) and one is of subtlety (passing through a gate). Whenever there is only one test or when the test taken is of activity or patience, the Akkoa light the candle in the last taken direction, originally established by the passage from the marked candle to the first test. When two tests present themselves and the test taken is of subtlety, the order of lighting reverses, beginning with the marked candle and passing into the unlit direction. The number of candles lit in the end corresponds to the number of tests of the path; only the long paths leave all candles lit.

By the Akkoaic system, the long paths play out as such. In the anointed path to the temple, the mark is placed on the third-left candle, then the second-left candle is lit, then the leftmost, then linearly from the rightmost candle to the mark all the candles are lit. In the submerged path, the mark is placed on the leftmost candle, then linearly all the candles are lit from the second-left candle rightward, until finally the leftmost candle is lit. The anointed path to love is the exact mirror of the submerged path to the temple, and the submerged path to love, of the anointed path to the temple. The pair are perfect reflections. Finally, the long path to the law begins by marking the leftmost candle, then lighting each candle one-by-one from right to left, until, as with the others, finishing at the mark.

With the centralized convention of the Temple for the first time under Dorothy Wood, the Temple itself came into possession of an exquisite candelabrum which came to be known as the Wick-Week. The lighting of a long path on this candelabrum became the condition of the iteration of a weekly counter, which rose very rapidly in early times. Yet the rituals of the week quickly complicated. A distinct faction within the Temple, which argued that a path cannot be understood except within the complete binomic context of a lemur, argued successfully to make invoking all the paths of a long path’s lemur standard practice. From there, the process was further complicated by a method of dealing with each test more distinctly: after having lit the first test, the lemur for whom the first test is a path would have all its paths be lit; after the first and second tests, the lemur for whom the first and second paths together are a test would have all its paths lit; and so forth. This second process meant the invocation of the five long paths included every lemur of Chronos except 8::1, for whom it became standard practice to light, and then snuff, the third-left candle after marking it for the anointed path of the temple.

Added to all this spiralling complexity were poems and songs of opening and closing, of the tests, of the lemurs, and of the paths. The result was a ritual process which was, sometimes, spaced out over a week of terrestrial days. This event was what prompted the beginning of Akkoaic liturgy, and with it, a context for interpreting the paths which continues to be broadly tapped in contemporary Neo-Lemurianism. And, of course, it was the first time the seven-armed candelabrum was thoroughly mapped in the Neo-Lemurian tradition—a form of mapping which has since been redone and redone again; the beginning of a wellspring of ritual.